In August of 2023, Cellebrite pushed a fork of a tool called SandBlaster, which decompiles iOS sandbox profiles from a proprietary binary format to a human-readable format. While running the tool is straightforward, the documentation doesn't explain where or how to obtain the binary blobs that contain all of the sandbox rules, so we hope to fix that now.

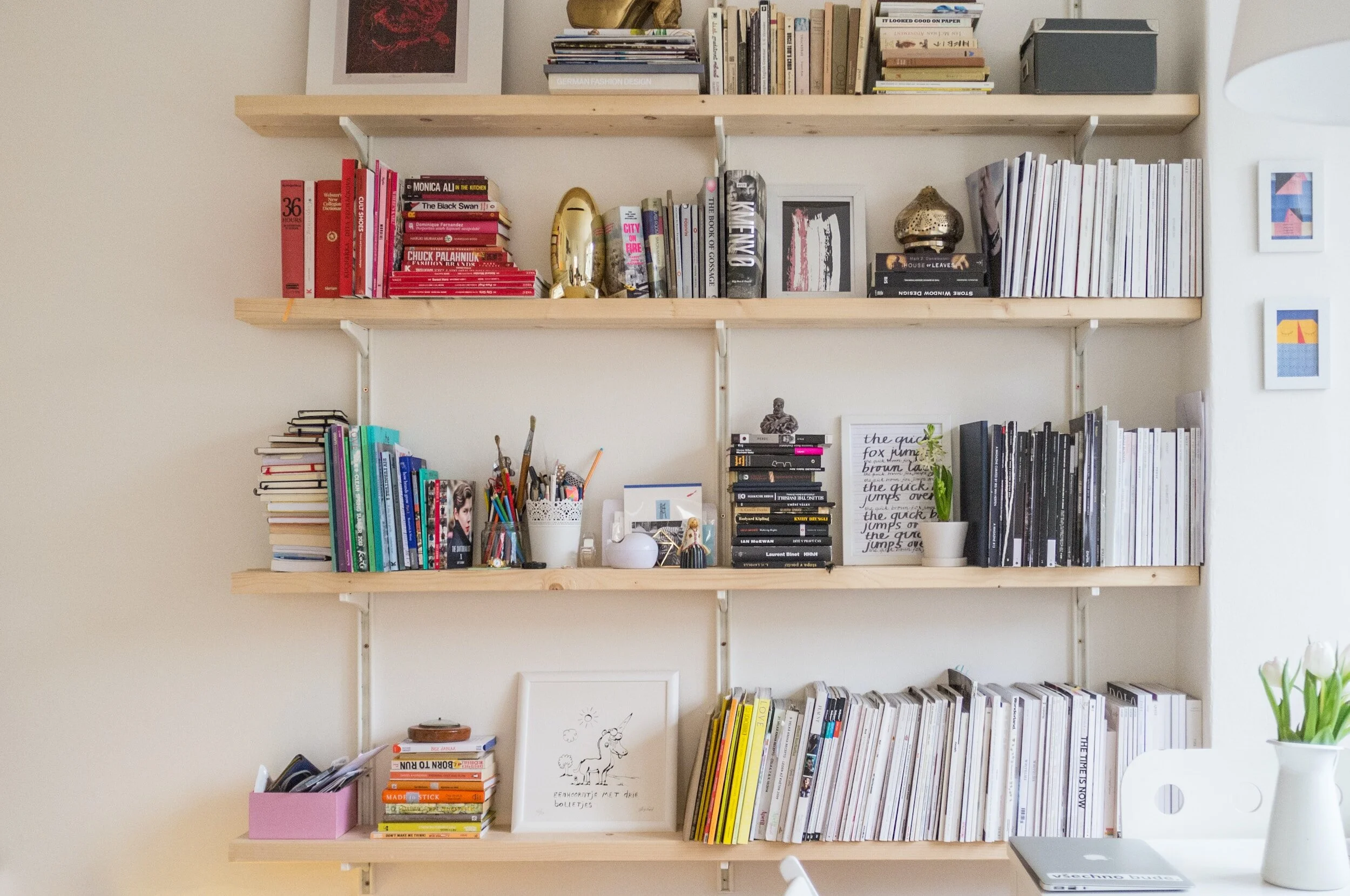

Read MoreArticles, blog posts, and books that we’ve found interesting in January 2024

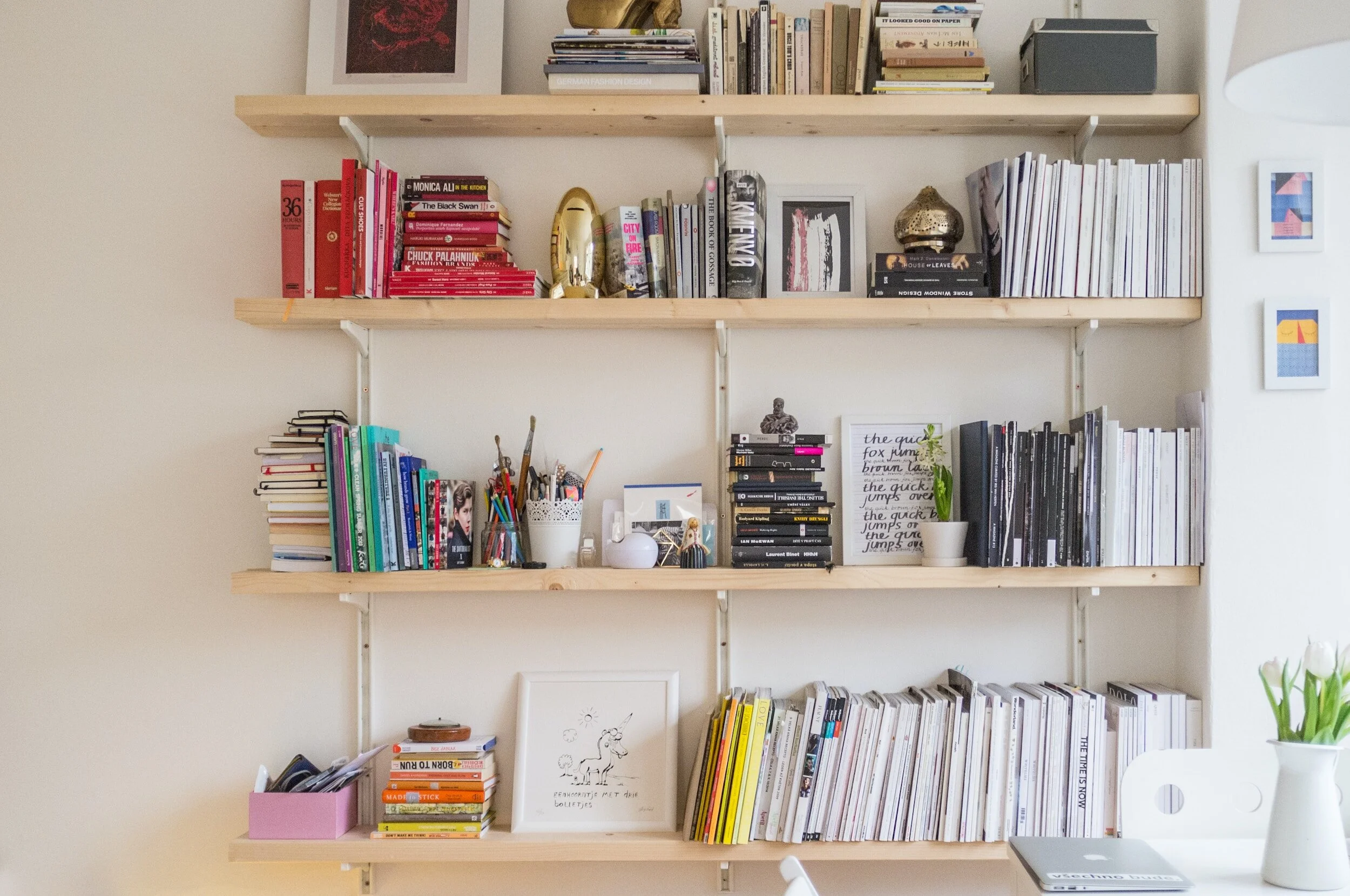

Read MoreArticles, blog posts, and books that we’ve found interesting in December 2023

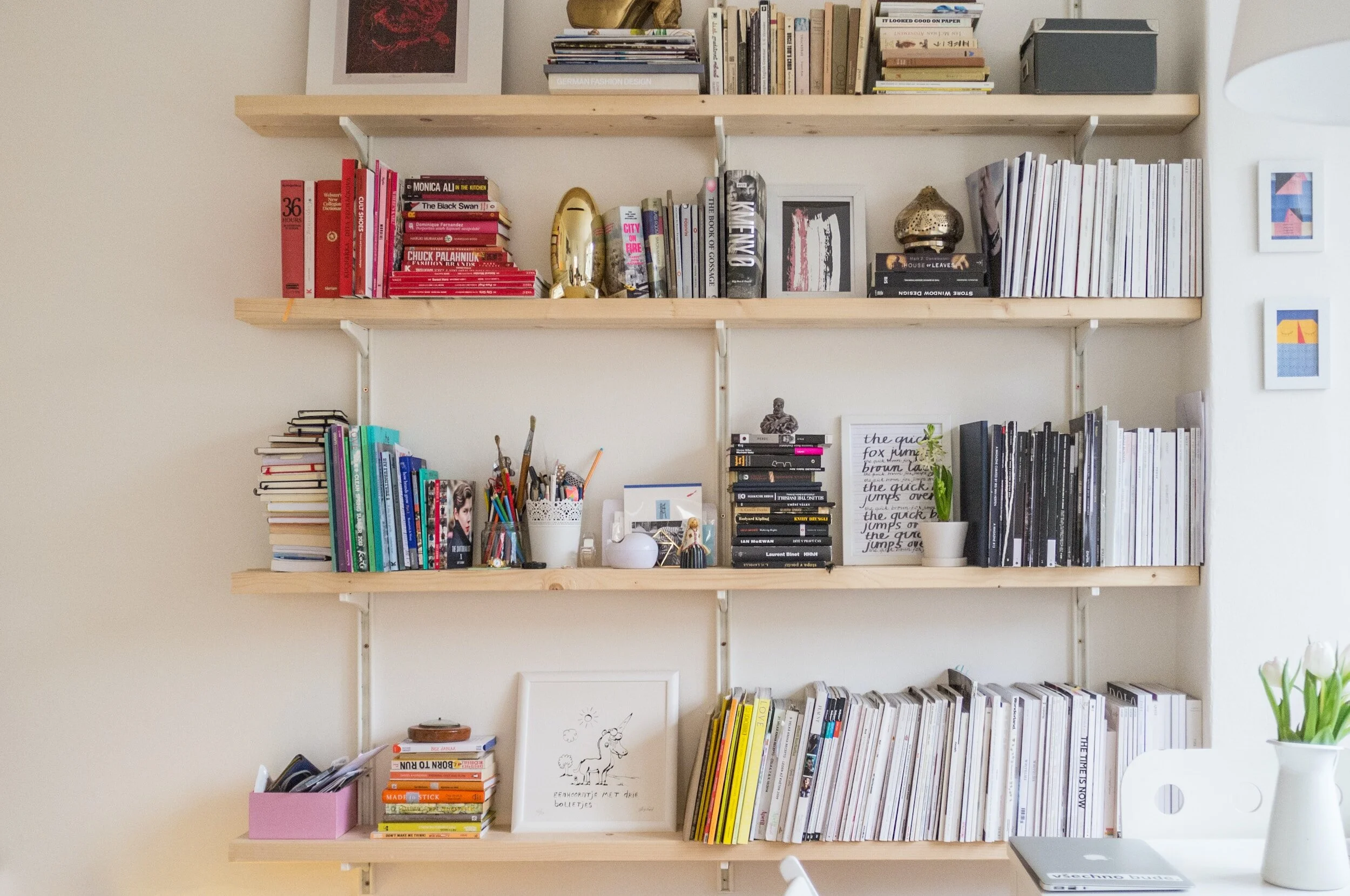

Read MoreArticles, blog posts, and books that we’ve found interesting in November 2023

Read MoreWhile playing with Corellium to practice developing exploits with previously-patched bugs, I started to think about how Corellium's hypervisor magic could be used to practice on generalized techniques even without an underlying vulnerability.

In the browser world, a typical exploit strategy would take two ArrayBuffer objects and point the backing store pointer from one at the other, such that arrayBuffer1 can change arrayBuffer2->backing_store_pointer arbitrarily and safely.

The iOS kernel, having a BSD component, contains an obvious equivalent: UNIX pipes. The pipe APIs are used much like files in typical UNIX fashion, but rather than being backed by a file on disk, their contents are stored in the kernel's address space in the form of a "pipe buffer" which is a separate allocation (by default 512 bytes, but can be expanded by writing more data to the pipe). Controlling the pipe buffer pointer creates arbitrary read/write primitives in the same way as controlling an ArrayBuffer's backing store pointer in a Javascript engine.

In November of 2019, I attended Ret2 Systems’ Advanced Browser Exploitation in Troy, New York, learning in great detail about the internals of Google Chrome’s V8 and Apple Safari’s JavaScriptCore. At the end of the five day course, we ended by implementing a full Chrome exploit that popped xcalculator as long as the sandbox was disabled.

A few weeks later, a shiny new car arrived. One of the first things I noticed? A Chromium-based browser that was severely out of date.

This seemed like an excellent application of the skills from the training, so I started to monitor Tesla’s updates and watch for V8 patches that could be used as the basis for an exploit. The project fell to the back burner for awhile, until an Exodus Intelligence blog post caught my eye at the end of February 2020.

By this time, Tesla had released several software updates, bringing Chromium to 79.0.3945.88 in their 2020.4.1 release. Since the Tesla software predated Google’s patch by a few weeks, it seemed pretty likely that the in-car browser would be vulnerable! Since Exodus provided a full exploit, the first 90% was done, and all the remained was the second 90% of porting over to the Tesla.

Read More